Overview

Central Texas lakes are collecting plastic litter and tire-wear particles, especially along brush-filled shorelines where existing cleanup boats can’t maneuver safely. Our Lake Guardians team set out to design a small, deployable system that can reach those pockets, corral floating plastics, and hand debris off to existing crews instead of replacing them.

Over two semesters, we’ve treated this as a full design-methodology case study: interviewing stakeholders from the City of Austin and UT research groups, translating quotes into customer needs, building engineering specifications and a House of Quality, then using structured concept generation and selection to arrive at a remotely operated airboat with a front comb bulldozer mechanism.

Design Methodology

This project is less about a single cool prototype and more about doing the design process correctly end-to-end. We:

- Conducted solution-neutral interviews and field observations, then converted raw quotes into interpreted needs, engineering requirements, and ranked specifications

- Built a House of Quality that benchmarked Mr. Trash Wheel, StormX Netting Trap, and Seabin, then used that to set target metrics for capture performance, ecological safety, and ease of maintenance

- Used function decomposition to break “remove plastics from lakes” into eight primary functions like intercepting floating plastics, protecting wildlife, retaining debris, enabling modular deployment, and informing the public

- Ran multiple ideation methods (6-3-5 brainwriting, design-by-analogy, SCAMPER) and captured those ideas in a morphological matrix and five fully defined concept variants

- Evaluated concepts with rotating-datum Pugh charts, backed by quick “back-of-the-envelope” calculations for throughput, capacity, cost, and maintenability

The outcome of all that structure was a clear, defensible choice: an airboat concept that balanced plastic removal, wildlife safety, cost, and maintainability better than drones, floating channels, or hand tools.

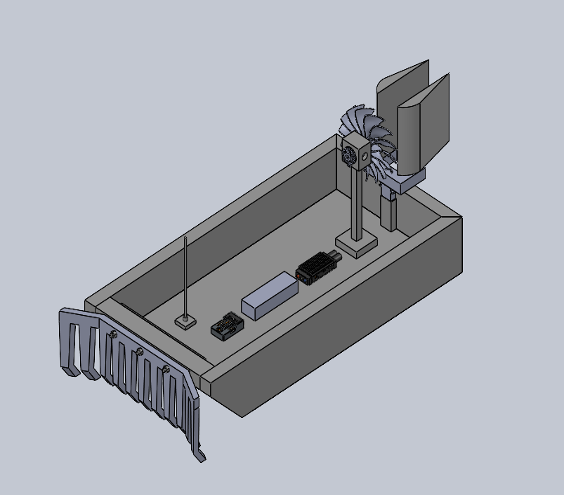

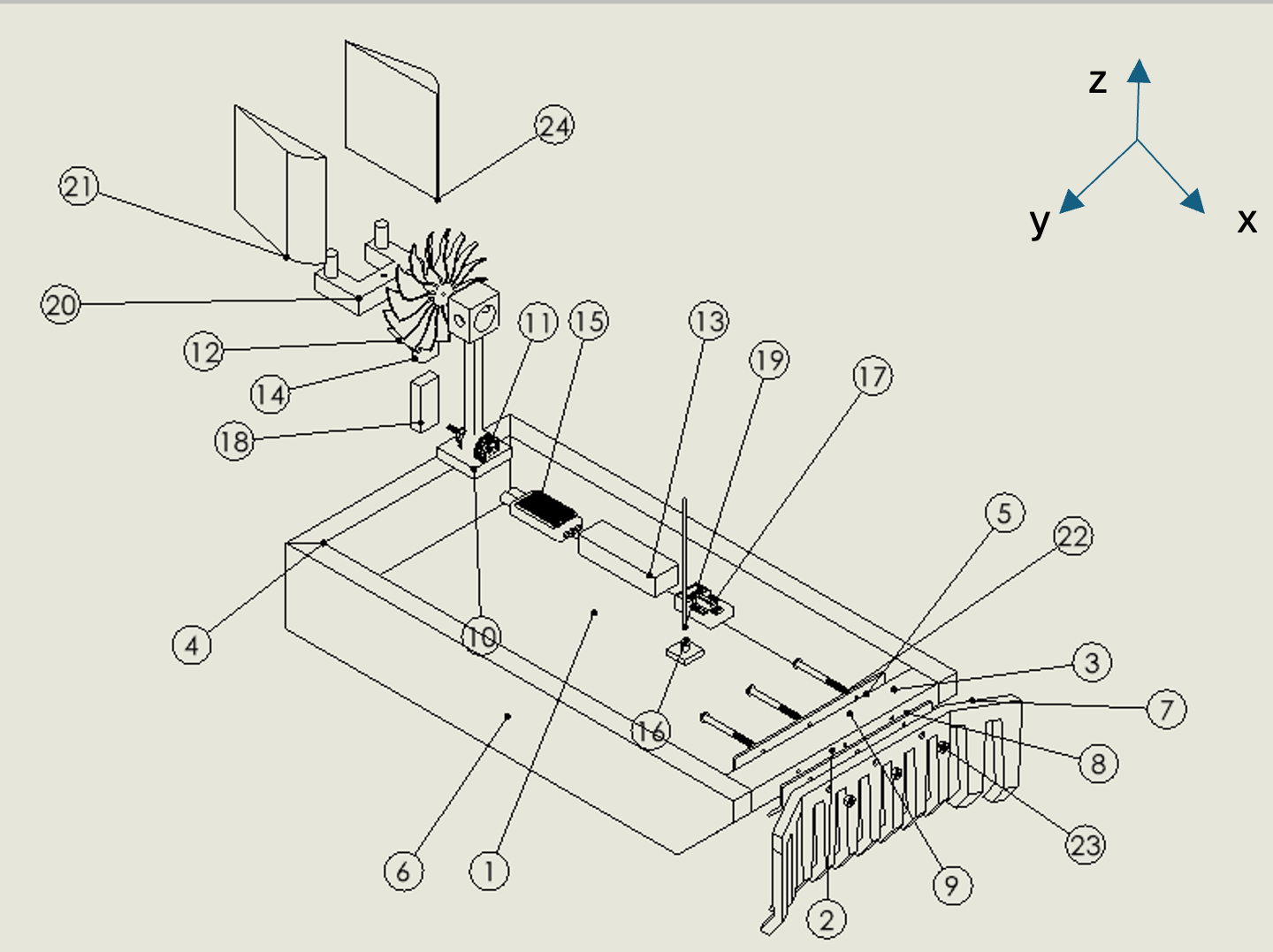

Leading Concept: Airboat Cleanup System

The final concept is a small airboat that pushes trash instead of sucking water:

- Above-water propulsion: a rear fan and rudder system mounted entirely above the waterline to avoid vegetation jams and protect wildlife

- Front comb bulldozer: a wide rake that funnels floating plastics out of brushy shorelines into access zones where crews can collect them

- Modular hull: stacked XPS foam panels with an epoxy skin, sized for a 2 ft × 1 ft footprint so the boat is stable, portable, and cheap to build

- Swap-in modules: a removable comb assembly, electronics pod, and propulsion module so parts can be upgraded or replaced without rebuilding the hull

Prototyping & Risk Reduction

Before spending real money on electronics, we built low-fidelity prototypes for the two riskiest subsystems: the comb and the hull.

- Comb prototype: PVC frame and paint-stick “teeth” tested in brushy, lake-like conditions with bottles and wrappers. This validated the geometry for pushing debris through vegetation and exposed obvious failure modes like tooth breakage and weak attachments

- Foam hull PoC: a bathtub-tested insulation-foam hull with a toy fan to confirm buoyancy, stability, and deck geometry before committing to a full epoxy-coated build

- FMEA: quantified risk around vegetation jams, electronics flooding, and RC signal loss, then drove concrete mitigations like a wiper system on the comb, sealed electronics enclosures, and antenna placement changes

Design for Manufacturing & Assembly

A big chunk of this project was learning to design for the shop we actually have, not the shop we wish we had. I leaned heavily on DFMA heuristics while revising the CAD:

- Manufacturing: re-designed the hull around flat XPS sheets and simple 2D cuts; converted the comb from many unique tines into a small set of repeated laser-cut panels; and selected common materials (foam, plywood, PVC, aluminum) that can be manufactured in student shops

- Assembly: reduced part count, consolidated bolt sizes, and added self-locating features and press-fit interfaces so the boat can be assembled top-down with simple hand tools

- Documentation: created detailed assembly drawings, an assembly plan, and a BOM that someone else could realistically follow without our whole report as a crutch

Responsibilities & What I Learned

This project forced me to live inside a structured design process for months and keep the team moving. Key things I owned and learned:

- Design process discipline: keeping our work traceable from customer quotes → interpreted needs → engineering specs → design artifacts (function tree, HoQ, morph matrix, Pugh charts) → final concept

- Risk-aware design: using FMEA as a real design tool instead of a checkbox, then folding those risks back into geometry changes, enclosure decisions, and control-system failsafes

- DFMA mindset: learning to simplify geometry, standardize parts, and design fasteners and interfaces so that volunteers—not just engineers—can assemble and maintain the system

- Project planning: maintaining the Gantt chart and task list, breaking ambiguous deliverables into concrete tasks, and making sure our design work aligned with the course milestones and the two-semester roadmap

- Communicating decisions: packaging all of this into clear reports and presentations so faculty, stakeholders, and future teams can understand why we chose an airboat, how it meets specs, and where to iterate next

Impact & Next Steps

By the end of the CDR, we have more than just a sketch: we have a justified, manufacturable airboat concept with drawings, risk mitigations, and a build plan. Next semester we’ll fabricate a medium-fidelity prototype, validate thrust and steering on the water, stress-test the comb in real vegetation, and close the loop with the researchers and city partners who helped shape the specs.

This project is the bridge between classroom design tools and the messy, constrained reality of environmental hardware: taking a vague goal like “clean the lake,” grinding it through formal design methodology, and ending up with something real that crews can deploy.

alt="Plastic debris along a vegetated shoreline on Lady Bird Lake" />

alt="Plastic debris along a vegetated shoreline on Lady Bird Lake" />